Spatial analysis demands precision, and area-based error assessment has emerged as a fundamental approach to ensure accuracy in geographic information systems and remote sensing applications.

🎯 The Foundation of Area-Based Error Assessment

Understanding how to measure and minimize errors in spatial data has become increasingly critical as we rely more heavily on geographic information for decision-making. Area-based error assessment provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the accuracy of spatial analyses, particularly when dealing with land cover classification, change detection, and predictive modeling. Unlike point-based methods that only sample specific locations, area-based approaches consider the spatial distribution and configuration of errors across entire regions.

The traditional approach to accuracy assessment often focused on pixel-level comparisons, which, while useful, failed to capture the spatial relationships and contextual information that are essential for understanding real-world applications. Area-based methods address this limitation by considering neighborhoods, patches, and regions as analytical units, providing insights that are more aligned with how spatial phenomena actually manifest in nature.

Why Traditional Point-Based Methods Fall Short

Point-based accuracy metrics have served the geospatial community for decades, but they come with inherent limitations that can lead to misleading conclusions. When we evaluate spatial data using only individual pixels or points, we ignore the spatial autocorrelation that exists in most geographic phenomena. Features in the real world rarely exist in isolation – forests connect to forests, urban areas sprawl across landscapes, and water bodies flow through watersheds.

This spatial dependency means that errors in classification or measurement are often clustered rather than randomly distributed. A point-based approach might indicate high overall accuracy while missing systematic errors that affect entire regions. For instance, if an algorithm consistently misclassifies forest edges as grassland, point sampling might only capture a few of these errors, underestimating the true impact on area calculations and landscape pattern analysis.

🔍 Core Principles of Area-Based Evaluation

Area-based error assessment operates on several fundamental principles that distinguish it from simpler methods. First, it recognizes that the spatial arrangement of correctly and incorrectly classified areas matters as much as their total quantity. A scattered distribution of errors has different implications than concentrated error zones, even if the overall error rate is identical.

Second, area-based methods acknowledge that different applications have varying tolerance levels for different types of errors. Agricultural monitoring might prioritize accurate field boundary delineation, while forestry applications might focus more on total canopy coverage. The assessment framework must be flexible enough to accommodate these varied priorities.

Spatial Accuracy Metrics That Matter

Several key metrics form the backbone of area-based error assessment. The confusion matrix remains foundational, but area-based approaches extend it by incorporating spatial weighting functions. Producer’s accuracy and user’s accuracy take on new dimensions when calculated for spatial units rather than individual pixels. These metrics help identify not just what was misclassified, but where systematic biases occur across the landscape.

Allocation and quantity disagreement decomposition, popularized by researchers in landscape ecology, separates errors into two meaningful categories. Quantity disagreement occurs when the total amount of a class is incorrect, while allocation disagreement happens when the right amount exists but in the wrong locations. This distinction is crucial for diagnosing classification algorithm performance and guiding improvement efforts.

Implementing Robust Assessment Frameworks

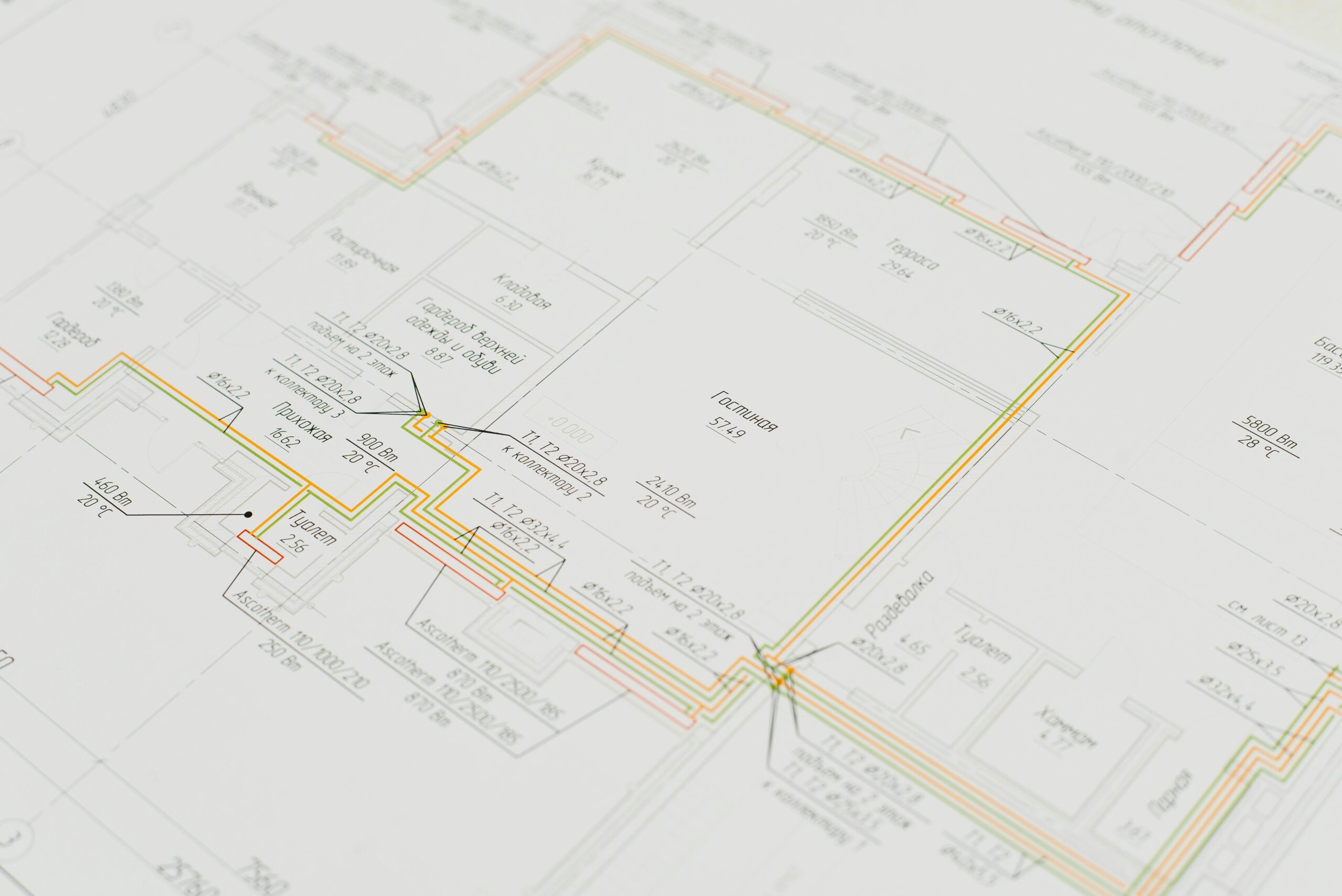

Establishing an effective area-based error assessment system requires careful planning and systematic execution. The first step involves defining appropriate spatial units for analysis. These might be grid cells of varying sizes, natural landscape patches, administrative boundaries, or functionally defined regions depending on the application context.

Reference data collection presents unique challenges for area-based assessment. While point sampling can rely on high-resolution imagery or field visits to verify individual locations, area-based validation requires comprehensive coverage of validation regions. This often necessitates combining multiple data sources, including aerial photography, ground surveys, and existing high-quality datasets.

Stratified Sampling Strategies

Given the impracticality of validating entire study areas, stratified sampling becomes essential. The stratification should reflect the spatial heterogeneity of the landscape and the expected error distribution. Areas with complex land cover mosaics might require more intensive sampling than homogeneous regions. Urban-rural transition zones, ecotones, and areas with rapid change typically deserve special attention in the sampling design.

- Stratify based on landscape complexity and classification confidence levels

- Allocate more validation samples to rare but important classes

- Include samples from error-prone boundary regions and transition zones

- Balance spatial coverage with class representation requirements

- Document sampling protocols thoroughly for reproducibility

📊 Advanced Techniques for Spatial Error Analysis

Modern area-based error assessment leverages sophisticated analytical techniques that go beyond simple accuracy percentages. Spatial autocorrelation analysis reveals whether errors cluster in particular regions, suggesting systematic issues with classification algorithms or input data quality. Moran’s I and local indicators of spatial association help identify error hotspots that warrant further investigation.

Fuzzy accuracy assessment recognizes that boundaries in nature are often gradual rather than abrupt. A pixel classified as forest at the edge of a grassland might not be entirely wrong, even if the reference data labels it differently. Fuzzy methods assign partial credit based on the likelihood that multiple classes could legitimately occupy the same location, providing a more nuanced evaluation.

Multi-Scale Error Characterization

Errors often exhibit scale-dependent patterns that single-resolution analysis cannot capture. What appears as random noise at fine scales might reveal systematic bias at coarser resolutions. Multi-scale assessment involves aggregating data and errors to various spatial resolutions, then examining how accuracy metrics change across scales. This approach helps determine the appropriate scale for specific applications and identifies the native resolution at which classification performs optimally.

Practical Applications Across Disciplines

Area-based error assessment finds applications across diverse fields where spatial accuracy matters. In agriculture, precision farming depends on accurate field delineation and crop type mapping. Understanding where and why classification errors occur helps optimize irrigation systems, fertilizer application, and yield predictions. Small errors in field boundary detection can translate into significant economic impacts when multiplied across large farming operations.

Urban planning and management rely heavily on accurate land use and land cover data. Area-based assessment helps planners understand not just overall mapping accuracy, but whether errors concentrate in particular neighborhoods or land use types. This information guides targeted updates and improves the reliability of urban growth models and infrastructure planning tools.

Environmental Monitoring and Conservation

Conservation efforts increasingly depend on remote sensing for habitat mapping and change detection. Area-based error assessment helps determine whether protected areas are accurately delineated and whether habitat fragmentation metrics can be trusted. When monitoring deforestation or wetland loss, understanding the spatial distribution of errors prevents false alarms and ensures limited resources focus on genuine threats.

Climate change research utilizes area-based methods to validate land surface models and carbon stock estimates. Forest carbon accounting, in particular, requires precise area measurements since carbon credits translate directly into financial value. Area-based assessment identifies regions where additional field sampling or improved classification methods are needed to meet reporting requirements and international standards.

🛠️ Tools and Technologies for Implementation

Numerous software platforms and libraries support area-based error assessment workflows. Geographic Information Systems like QGIS and ArcGIS provide foundational tools for spatial analysis and accuracy assessment. However, more specialized approaches often require programming environments that offer greater flexibility and automation capabilities.

Python has emerged as a preferred platform, with libraries like scikit-learn for machine learning metrics, numpy and pandas for data manipulation, and specialized packages like rasterstats and geopandas for spatial operations. R provides similar capabilities through packages like caret, sp, raster, and landscapemetrics, the latter being particularly valuable for landscape-level spatial pattern analysis.

Workflow Automation and Reproducibility

As spatial datasets grow larger and analysis becomes more complex, workflow automation becomes essential. Creating reproducible pipelines ensures that error assessment can be consistently applied across multiple time periods, regions, or classification approaches. Version control systems help track changes in methodology and facilitate collaboration among research teams.

Cloud computing platforms have revolutionized the scale at which area-based assessment can be conducted. Google Earth Engine, for instance, enables continental-scale accuracy assessment that would be impractical on local computing infrastructure. These platforms combine vast archives of satellite imagery with parallel processing capabilities, making comprehensive spatial error analysis accessible to researchers who lack extensive computing resources.

Overcoming Common Challenges and Pitfalls

Implementing area-based error assessment is not without challenges. Registration errors between reference and classified datasets can artificially inflate error estimates, particularly along boundaries. Even small positional discrepancies can cause correctly classified areas to appear incorrect when comparing pixel-by-pixel. Fuzzy boundary methods and edge-aware metrics help mitigate this issue but require additional computational effort.

Temporal mismatches between reference data collection and image acquisition dates can also complicate assessment. Landscapes change, sometimes rapidly, and what appears as a classification error might actually reflect genuine change that occurred between data collection times. Careful documentation of data provenance and temporal metadata helps distinguish true errors from temporal artifacts.

Balancing Comprehensiveness and Practicality

The most comprehensive error assessment would validate every pixel or polygon across the entire study area, but resource constraints make this impossible for most projects. Finding the right balance between statistical rigor and practical feasibility requires thoughtful experimental design. Power analysis can help determine minimum sample sizes needed to detect meaningful differences in accuracy between methods or time periods.

Cost considerations extend beyond just the assessment itself. High-accuracy reference data collection can consume substantial portions of project budgets. Leveraging existing datasets, crowdsourced information, and automated quality checks can help manage costs while maintaining adequate validation standards. The key is ensuring that cost-saving measures don’t undermine the reliability of the assessment.

🌍 Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of area-based error assessment continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in artificial intelligence, sensor technology, and computational capacity. Deep learning approaches now enable more sophisticated error prediction models that can identify likely error regions before expensive field validation occurs. These models learn from patterns in correctly and incorrectly classified areas, helping prioritize validation efforts where they’ll provide maximum value.

Integration of multiple data sources through data fusion techniques offers new opportunities for improving both classification accuracy and error assessment. Combining optical satellite imagery with radar data, LiDAR point clouds, and ancillary datasets creates richer information bases that reduce ambiguity in classification. Multi-source assessment frameworks help understand how different data types contribute to overall accuracy and where each performs optimally.

Citizen Science and Collaborative Validation

Crowdsourced validation platforms are democratizing error assessment by enabling large-scale reference data collection through volunteer contributions. Projects like Geo-Wiki and LACO-Wiki harness collective intelligence to validate land cover products across vast areas. While quality control remains crucial, these approaches can achieve coverage levels that would be prohibitively expensive through traditional means.

Mobile applications equipped with GPS and camera capabilities make field validation more accessible and systematic. Teams can efficiently collect georeferenced photos and observations that feed directly into assessment databases. This real-time validation supports adaptive sampling strategies where initial results guide subsequent field visits to areas with unexpected errors or ambiguous classifications.

Making Area-Based Assessment Accessible and Actionable

For area-based error assessment to reach its full potential, it must become more accessible to practitioners who may lack extensive technical expertise. User-friendly tools and clear documentation lower barriers to implementation, ensuring that rigorous spatial accuracy evaluation becomes standard practice rather than an optional extra. Educational resources, including tutorials, workshops, and case studies, help build capacity across disciplines.

Standardization efforts through organizations like the International Organization for Standardization and the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites promote consistent methodology and reporting. These standards facilitate comparison across studies and help establish minimum quality thresholds for operational applications. As spatial data increasingly informs policy and decision-making, such standards become not just helpful but essential.

Transforming Data Quality into Decision Confidence

Ultimately, area-based error assessment serves a larger purpose: transforming uncertainty about spatial data quality into confidence in decisions based on that data. When stakeholders understand not just overall accuracy but the spatial distribution of reliability, they can make more informed choices about where to trust the data fully and where to exercise caution or collect additional information.

This transparency about uncertainty builds credibility and trust in spatial analysis products. Rather than presenting classifications as definitive truth, acknowledging and characterizing errors demonstrates scientific integrity and helps users understand appropriate applications and limitations. Well-executed error assessment thus becomes not just a technical exercise but a communication tool that bridges the gap between spatial analysts and decision-makers.

The journey toward mastering precision in spatial analysis requires commitment to rigorous error assessment practices. Area-based methods provide the framework for this rigor, moving beyond simplistic accuracy metrics to capture the spatial complexity of how errors manifest across landscapes. As our reliance on spatial data continues to grow across agriculture, environmental management, urban planning, and countless other domains, the ability to accurately assess and communicate spatial uncertainty becomes increasingly valuable. Investing in robust area-based error assessment isn’t just about improving technical quality – it’s about ensuring that spatial information serves society effectively and responsibly.

Toni Santos is a data analyst and predictive research specialist focusing on manual data collection methodologies, the evolution of forecasting heuristics, and the spatial dimensions of analytical accuracy. Through a rigorous and evidence-based approach, Toni investigates how organizations have gathered, interpreted, and validated information to support decision-making — across industries, regions, and risk contexts. His work is grounded in a fascination with data not only as numbers, but as carriers of predictive insight. From manual collection frameworks to heuristic models and regional accuracy metrics, Toni uncovers the analytical and methodological tools through which organizations preserved their relationship with uncertainty and risk. With a background in quantitative analysis and forecasting history, Toni blends data evaluation with archival research to reveal how manual methods were used to shape strategy, transmit reliability, and encode analytical precision. As the creative mind behind kryvorias, Toni curates detailed assessments, predictive method studies, and strategic interpretations that revive the deep analytical ties between collection, forecasting, and risk-aware science. His work is a tribute to: The foundational rigor of Manual Data Collection Methodologies The evolving logic of Predictive Heuristics and Forecasting History The geographic dimension of Regional Accuracy Analysis The strategic framework of Risk Management and Decision Implications Whether you're a data historian, forecasting researcher, or curious practitioner of evidence-based decision wisdom, Toni invites you to explore the hidden roots of analytical knowledge — one dataset, one model, one insight at a time.